The Shapes of Railway Networks

I made this post on another site a while ago, and I really like it, so I thought I’d replicate it here. If you happen to know the original post, I couldn’t find the original images I had anymore, so I recreated them, and as a result they’re slightly different. But I think that shouldn’t matter to much.

The basic idea here is that you can tell a lot about a country and in particular its history during the 19th and early 20th century by its railway network. So let’s do that. And the best way to do that is by looking at the incredibly detailed open-source world railway map OpenRailwayMap, a part of the OpenStreetMap project. I really recommend it! Note, though, that some relevant rail lines aren’t shown at the zoom levels I’m using here, sometimes it’s a bit wonky. But anyway, let’s start with one of my favorite examples of how railway networks differ:

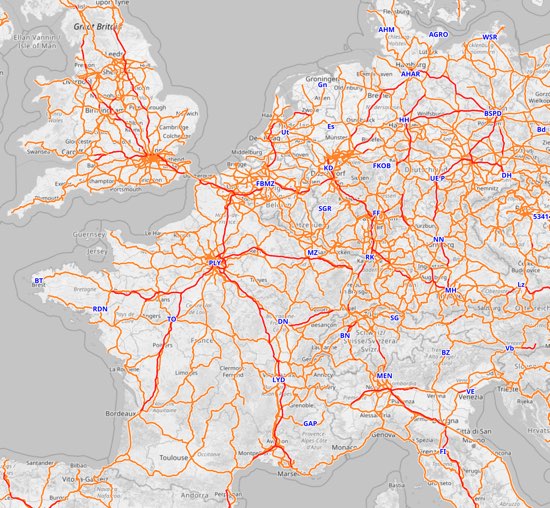

At this zoom level the site sadly only shows incomprehensible internal abbreviations rather than city names, so let me explain: What we have here are France and Germany, along with some of the UK and Italy, some of various neighbouring countries and all of Switzerland, Belgium and Luxembourg.

France and Germany are the ones that I find the most interesting, because the shapes of their networks are so different. Not only is the german one much more dense, but you can see completely different patterns.

In France, the job of railroads is to bring people to Paris (PLY, short for Paris Gare de Lyon) The lines stretch out into every part of the country, but almost all of them converge onto mainlines going into Paris. You can see some lines along the coasts and the borders, and there is a medium distances circle around Paris (passing MZ, DN, TO, short for Metz, Dijon, Tours). This whole pattern is known as the Legrande Star, after Baptiste Alexis Victor Legrande, the french government official who designed it. His goal was to provide great access to Paris, the nation’s undisputed political, cultural and economical centre. A couple of decades later, Charles de Freycinet added plans to connect all departments to the railway network, but he still followed the idea that the ultimate goal of almost every rail line was Paris. And so it was, and largely remained. Even the high speed lines, in red, follow this pattern to this day.

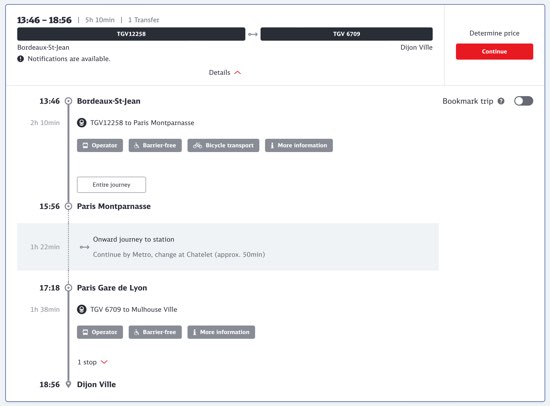

A result is that you will have to go to Paris whether you want to or not. Lille-Strasbourg? You’re going through Paris. Bordeaux-Dijon?

You’re going through Paris, and get to make your own way from Gare Montparnasse to Gare de Lyon on the Metro (and it isn’t even a direct metro, you have to change trains). It’s a massive detour but it’s not like you have a choice.

Even if there is a direct TGV or a connection outside the main stations of Paris, you’re still ending up very much near Paris; the difference is just that you’re not going via the city centre, but rather via Disneyland. Legrande wanted to bring people to Paris; he was less concerned about connecting other places with each other.

Now compare Germany, and you will see a network that is more dense, but most importantly, utterly chaotic. You can see hints of a France-like star around Berlin (BSPD, short for Berlin Spandau, which isn’t the most important station but what can you do), but it’s really only dominating its immediate surroundings, the region of Brandenburg. You can see vague hints of a similar star around Hamburg (AHAR; don’t ask) or Munich (MH), but also a massive tangle around the Rhine-Ruhr industrial area (around KD), or around the Frankfurt am Main area (FF). Red high speed lines are essentially random. Some of them do go to Berlin, sure. But many, like the one from Cologne to Frankfurt (KD to FF) or the one from Hanover (HH) south, do not.

And that really reflects the history. Germany wasn’t a unified country when railroad construction began, and even though it did unify shortly thereafter, there’s no hiding that its different parts developed separately, with no central planning, ever since the middle ages. Germany doesn’t have a single central city like France. Berlin is the biggest and most important city, but not by far. Hamburg has huge cultural and industrial influence, Frankfurt is the most important financial centre and airport, Munich is huge, and there are agglomerations like the Rhine-Ruhr region that used to beat all of them in terms of industry. And the rail network, with no single central focus point, reflects that.

That doesn’t mean Germany doesn’t have its own blind spots. Due to being split in two, the east-west links aren’t great. Getting e.g. from Cologne (near KD) to Dresden (DH) is pretty painful. Ironically, Berlin is one of the places that really suffers from this. There are plenty of trains to it from Cologne but they take forever, and you can see why: A lot of the route isn’t high speed, it’s just more or less upgraded normal lines. If you have a single destination, then it’s easy to build all the lines there. If you want high-speed connections between everything, that’s more difficult. (Also, our government isn’t investing anywhere near enough into the rail network, both compared internationally and on its own terms, but that’s a different issue)

Other countries in Europe tend to be somewhere between the extremes. Spain is fairly centralised around Madrid.

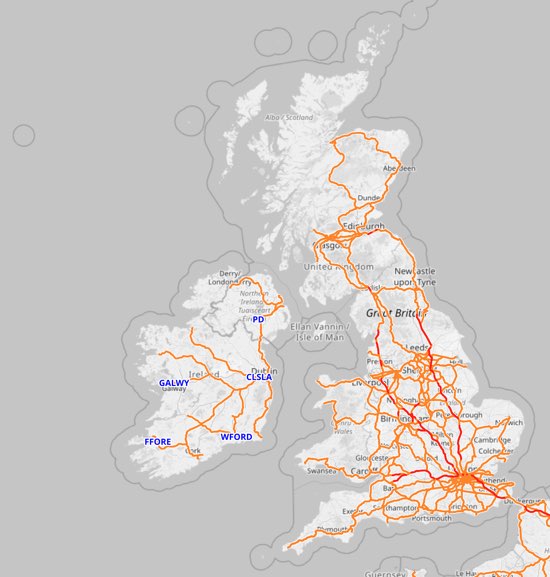

The UK is just as focused on London as France is on Paris, but it has strong regional networks around Leeds and Sheffield, and some weirdness in Scotland (four different lines between Glasgow and Edinburgh and counting!).

Italy, especially south of the Po valley, almost looks like a ladder: Lines are either on the one side of the Apennines or the other, with a few select ones crossing through, and a red high speed spine that finds its own axis in the middle.

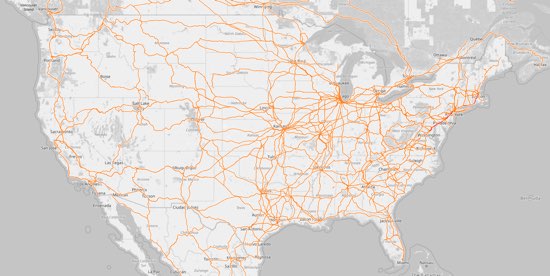

This works overseas as well. Describing the continental US as “like Germany” is certainly going to raise some eyebrows, but the map doesn’t lie:

It’s all on a completely different scale, but it’s also a federal country with no one single clear centre. Yes, New York and Los Angeles are big and important, but neither is an all-powerful centre of the nation. What’s fun about the US is that it’s almost gradient-like: The more west you go, the fewer the railroads get. You can also nicely see the Alleghenies by the shadow they cast: Building lines through there or around them is expensive, so very few do. Other characteristic items are the huge tangle that is Chicago, the closest thing the US has to a railroad capital; and the many places where lines are almost duplicated (just count how many different ways you can get from Chicago to Memphis, or Chicago to Cleveland), thanks to different competing railway companies that all hated (and sometimes still hate) each other’s guts.

So that’s what’s mostly considered the “western world” or “industrialised world”. I skipped Japan, China and India because the post is going to get too long no matter what, but they’re all fascinating as well.

But if we go away from there look at countries where the colonialism was less settlers and more exploit mostly from afar, we see another very odd pattern emerge, like here in sub-saharan Africa:

The selection is somewhat arbitrary because you can find the same pattern everywhere south of the Sahara, and in one case (Mauretania) even in the Sahara: A railroad that goes straight to the coast. Note that the isolated sections inland are due to issues with the map software, they’re all connected to one of the lines to the coast; and also some of them used to be longer when I made the original post earlier this year. If you zoom in, it’s all there, but apparently some of the lines are now disused.

This kind of railroad is designed to extract a country’s resources, and not much else. In Mauretania (not in this picture), that’s iron ore. Elsewhere it might have been other ores, precious metals, gemstones, but also very often agricultural products, spices, dyes. The railway line exists to take these things and bring them to a port. It is not designed to actually help the nation grow economically.

Think about it: All things being equal, you’re probably just as likely to want to go parallel to the coast as perpendicular to it, but the railways don’t facilitate that. Yes, coastal shipping is a thing, but loading things onto ships costs time and effort (aka money). Most more developed countries I’ve shown have lines that parallel coasts, either directly at the shore or a bit inland.

Also, each of these lines were built because there’s something interesting at the end of it, or at least someone suspected there might be. If you wanted to develop the area, it would make sense to trade the interesting stuff in Togo with the interesting stuff in Benin. But the railway lines are not set up for that at all. The goal is to get the interesting stuff to a ship, and occasionally soldiers to the place where the interesting stuff comes from.

These days, the area that I screenshotted here is actually a massive region full of people. The city of Abidjan has more than four million inhabitants (more than Berlin), Lomé has 1.7 million, Cotonou and Porto-Novo come close to a million if taken together, and nobody’s quite sure about Lagos, but it’s at least 14 million, and the metropolitan region might be 24 million. This is a band of cities that researchers think might, in the next few decades, become on par with Washington-Philadelphia-New York-Boston in the US, or the Tokyo-Osaka in Japan.

And the rail connections in this region do not reflect this at all. A high speed passenger line and/or a heavy duty freight line could allow all these places to do business with each other, allow people to move to or visit each other, and just spur a lot of economic development. But the powers that built the lines, the colonial powers, were not interested. They had their harbour, and the region behind it, and they just wanted to extract whatever was there.

To be clear, that does not mean the railroads are evil now. Selling natural resources is still better than bringing no money into the country. And there are a lot of places where railroad junctions and depots became the point where cities were founded, so in some countries these lines do end up connecting the most important cities, more or less by accident. It’s just that other lines or more lines are sorely missing.

A simple example for how this could look like is provided by Australia, where the colonists were settlers and did want to develop the land economically:

You have the lines from the coast inland, and sometimes quite a lot of them. But you can also see a line along the east coast, connecting the cities, and you can see that someone said “we need to build a railroad across the entire continent. No, two actually”. That is not to say that Australia does everything right with railroads, they have a lot of weirdness there. But you can see that the railroads had more jobs than to just move resources to ships.

(The big exception is the Pilbara region, in the north west, with its odd tangle of lines. Those are all just resource extraction lines, where the world’s heaviest freight trains haul iron ore from various mines to various ports. The mines and ports are owned by different mining companies that don’t like each other, so everybody has their own line from their own harbour to their own mine, even if a different line would have been shorter.)

So, that’s basically it. The railroad map of a country shows you a lot about how a country works, and more specifically how it worked during the late 19th and early 20th century, when most railroads were built. Where they lead to and where they don’t reflects what connections planners thought of as important, and in turn, it has shaped the way these countries developed. And personally, I always find this endlessly fascinating.

Written on November 14th, 2023 at 07:57 pm

Deutsche Version

Deutsche Version